News & Announcements

Read the latest news, announcements and events, such as the Tribal Land Staff National Conference, CLE opportunities, land issues, and items in the press about activities of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and our grantees and affiliates.

Latest News

ILTF IS NOW HIRING FOR THE NATIONAL INDIAN CARBON COALITION PROGRAM

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF), a community-based organization with its headquarters located near St. Paul, Minnesota, is hiring for two positions for its National Indian Carbon Coaltion (NICC) program: Carbon Marketing Specialist and Project Manager (Reforestation). NICC is dedicated to combating climate change through carbon sequestration initiatives and innovative reforestation activities.

The Carbon Marketing Specialist will develop and execute marketing strategies to promote carbon-related products, services, and initiatives. This role involves creating compelling campaigns, educating the target audience about carbon-related concepts, and driving engagement to support carbon reduction and sustainability efforts. Click the link for a complete description of the Carbon Marketing Specialist position.

The Project Manager (Reforestation) specializes in developing carbon reforestation projects. The Project Manager will be responsbile for designing, implementing, and managing carbon offset projects that aim to establish and maintain forests and other natural ecosystems. Click the link for a complete description of the Reforestation Project Manager position.

——————————

ILTF ANNOUNCES BEYOND LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT FUND

Turning empty words into concrete action

Jan. 9, 2023

Little Canada, Minn. — Indigenous land acknowledgements are everywhere now as local governments, universities and other organizations regularly make statements at press conferences, community gatherings and public events acknowledging the historic taking of land by colonial settlers. To many Native Americans, these are just empty words. Now the Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is offering those who make land acknowledgements an opportunity to put their money where their mouth is.

“These organizations do the acknowledgement and figure that lets them off the hook,” said ILTF president Cris Stainbrook. “It alleviates their guilt a little I guess. The organization gets nice press coverage, but it never results in any change in behavior or any land back to the tribes. There needs to be some sort of action taken or the land acknowledgement is meaningless.”

In response, ILTF is launching the ‘Beyond Land Acknowledgement Fund’ to serve as a conduit for others – organizations, institutions, governments and the like – to turn talk into action.

Based in the Twin Cities, the Indian Land Tenure Foundation a national, community-based organization that has been serving American Indian nations and people in the recovery and control of their rightful homelands since 2002. It has played a key role in land return projects across the country, including the recent recovery of more than 28,000 acres by the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa.

Spawned by an unexpected gift

Initial funding for the Beyond Land Acknowledgement Fund came to ILTF through an unexpected donation from Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in Minneapolis. Stainbrook spoke to members of the congregation about Indian land issues last fall. When his presentation concluded, the pastor stepped forward to say thank you, read the congregation’s land acknowledgement out loud, and handed Stainbrook an envelope. “She said, ‘Here’s a little something to help you get land back.’ When I opened the envelope I was in shock.” Inside was a check to ILTF for $250,000.

“It blew me away,” said Stainbrook. “It shows that they aren’t just going to church on Sunday to talk about it. They are living their values. This is a community of people who are making a statement. It’s not just one person, it’s the body, it’s the whole. They need to be recognized for taking such a substantial step, for saying, ‘We are serious about this.’”

Many churches have engaged in learning and conversation with Indigenous communities in an attempt to build understanding and bridge longstanding gaps. For Pastor Ingrid Rasmussen and the congregation, there was a need to do more.

“For many years, Holy Trinity Lutheran Church has been publicly saying that ‘We gather on the Dakota Homeland,’” she explained. “More recently, church leaders crafted a longer land acknowledgment that states that the land our congregation currently occupies was taken from the Dakota Nation and other Indigenous peoples through exploitation and violence. Because our church benefited from the land theft, we recognize our responsibility to advocate for treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, and movements to return land back into Indigenous hands. The significance of this sacred ground – as well as its painful history – compels us as a congregation to engage in reparative justice in words and deeds and dollars.”

The donation came with no strings attached, but ILTF is seizing the opportunity to amplify the church’s generosity in a big way. “For those entities that want to put their money where their mouth is there hasn’t been a good vehicle to do that,” Stainbrook said. “To be fair, it hasn’t been easy. They can’t see themselves buying land and returning it. They wouldn’t know where to begin. The ILTF Beyond Land Acknowledgement Fund enables us to collectively pool that money to make purchases. It offers a vehicle for those entities who want to take that next step and actually do something about returning land and making it right.

Media contact: Grant McGinnis (gmcginnis@iltf.org)

Announcements

NEW ILTF WEBINARS

ILTF has webinars coming up in 2023 on a variety of topics. Look for an announcement soon for the first webinar of the year on Jan. 23, 2023.

News Archive

THE BETTER WAY TO RIGHT AN OLD WRONG

Aug. 26, 2022

By Cris Stainbrook

Land that was wrongly taken from tribes more than 100 years ago is often only returned if the tribes agree to adhere to someone else’s interpretation of what’s best for the land. There’s a better way to right an old wrong.

Imagine one day City Hall seized your home’s front and back yards, along with your driveway, front walk and back porch. Yes, you’d still have a house where you could eat, sleep and reside. But you’d no longer have your full home and what was rightly yours.

Now, imagine you were given the opportunity for that land to be returned to you. All you’d have to do is promise to never change a thing. You could maybe do something benign – pruning the trees or mowing the grass – but you could not build a shed, start a garden, or add a swing set for your children.

Would you take the deal?

This, in essence, is the deal Indian Country is commonly offered when land conservation organizations offer to return anywhere from 10 to 10,000 acres of land to Native American tribes. Land that was wrongly taken from tribes more than 100 years ago is often only returned if the tribes agree to adhere to someone else’s interpretation of what’s best

There’s a better way to right an old wrong.

Recently, two organizations, the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and The Conservation Fund, helped finalize a deal by which the Bois Forte Band reacquired 28,089 acres of its reservation land in northern Minnesota that was lost to federal allotment during the late 19th century. This deal is the single-largest private land restoration project in United States and Indian Country history based on available historical data. And that forestland went to the Band without any permanent obligations for the care, management or use of that land.

Some well-intentioned people with an honest desire to see beautiful land remain beautiful challenge this approach. They argue that a lack of permanent restrictions on the land means that trees could be cut down, factories could be built, or lakes could be fished to exhaustion.

But the Bois Forte Band is, and always has been, the best steward of this land. It is their home. It is precious to them, and caring for this land is paramount to them, irrespective of permanent obligations prescribed to them in a legal document, such as a conservation easement.

How do I know this to be true? Through close collaboration with the Band’s leadership, we built an understanding that is centered around listening and fully understanding their unique history, current challenges and vision for the future.

As an example, the Bois Forte Band first sought to safeguard their land by entering into treaties with the United States in 1854 and 1866 to establish a permanent and undisturbed homeland. But a few decades later, the federal government set aside its treaty obligations so it could divide the Band’s land, selling it to timber companies and homesteaders. After The Conservation Fund acquired over 72,000 acres of forest land in 2020 – with significant acreages of allotted reservation land – a unique opportunity took shape to help the Band regain 21 percent of its lost homeland, securing forever what should have been secure 156 years ago.

The Bois Forte Band expressed a unique passion for land conservation and an unquestionable commitment to do what’s best for the forest. Moreover, the Band was prudent in identifying and pursuing opportunities whereby it could financially benefit from keeping the land in its natural state. Acres enrolled in Minnesota’s Sustainable Forests Initiative Act, for example, will generate revenue for the Band.

The transaction further supports the Band’s sovereignty through full-faith-in-credit financing provided by Indian Land Tenure Foundation’s subsidiary, the Indian Land Capital Company, which allowed the Band to acquire the land without having to use it as collateral.

While there was no conservation easement in place on any of the land tracts, the Band was strongly incentivized to maintain these lands as a working forest. This symbiotic mindset goes to the Band’s benefit as much as it secures the forest’s future. In this way, the Band recognizes the forest as an environmental asset rather than a commodity to be consumed.

This arrangement need not be unique. Indeed, an approach that honors tribal sovereignty while incentivizing best practices in land conservation represents a new and gracious path forward for this type of work.

A better way to right this old wrong is by thinking differently. If the people, organizations and financial institutions involved in land restoration work are more willing to structure their deals and finance their transactions differently, we will more readily achieve the outcomes we — tribes and conservation groups — yearn to see.

This is how tribes such as the Bois Forte Band can regain lost land in a way that empowers and inspires – and it’s how we can work together to better right an old wrong.

Cris Stainbrook, Oglala Lakota, has been working in philanthropy for 35 years and has been President of Indian Land Tenure Foundation since its inception in 2002. Before joining ILTF, Stainbrook spent 13 years at Northwest Area Foundation, where he managed grant making programs in sustainable development, natural resource management, economic development and basic human needs.

———————————————-

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL: AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Aug. 3, 2022

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is requesting proposals for preparation of its yearly audited financial statements and related information for the 2022 fiscal year ending December 31, 2022. The audited financial statements must be prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. The audit must also include an expression of an opinion by the auditor on the fairness of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles.

ILTF is a 501(c)(3) Minnesota community foundation providing grants and services to federally-recognized Native American Tribes and other organizations working with Native American land issues throughout the United States. We receive funding from individuals, foundations, Native American Tribes and other organizations interested in helping us fulfill our mission. We also pursue funding from the federal government when the opportunity arises. ILTF is also a partner in the Indian Land Capital Company, a for-profit organization which it organized as a subsidiary to provide financial lending services in Indian Country.

ILTF requires the following services:

- Yearly financial audit, including

- Consolidated statement of financial position

- Consolidated statement of activities

- Consolidated statement of functional expenses

- Consolidated statement of cash flows

- Supplemental statements separating parent and subsidiary

- Single audit (if applicable)

- Preparation of IRS form 990

- Preparation of Charitable Organization Annual Report for the Minnesota Attorney General

- Preparation of subsidiary organization’s tax return for applicable states

- Management letter

The final audit report(s) and management letter must be completed within four months of the end of each fiscal year. The tax returns must be completed and filed by August 15. ILTF requires that a meeting of the auditors and selected ILTF staff be held to discuss a draft version of the audit. ILTF also requires that the auditors meet with ILTF’s Audit Committee each May in conjunction with our board of directors’ meeting.

All audit proposals must include:

- Firm’s qualifications to provide the above services

- Background and experience in auditing, particularly of nonprofits

- Size and organizational structure of auditor’s firm

- Statement of firm’s understanding of work to be performed, including tax and non-audit services

- A proposed timeline for fieldwork and final reporting

- Proposed fee structure for these services, with projected costs for future audits covering two additional years, with a maximum fee to be charged

- References from at least three comparable audit clients

Please email your proposal to dbordeaux@iltf.org or mail a hard copy to Indian Land Tenure Foundation, 151 Cty Rd B2 E in St. Paul, MN 55117. Proposals must be received by September 30, 2022. Our Audit Committee will review all proposals and make a recommendation regarding the choice of auditors to our full board of directors in early November.

If you have any questions or would like further clarification of this request for proposals, please contact D’Arcy Bordeaux at 651-789-1742.

———————————————

NEWS RELEASE

BOIS FORTE BAND REGAINS HISTORIC TRIBAL LAND

Partnership between Band, The Conservation Fund, Indian Land Tenure Foundation restores ownership of 28,089 acres of reservation land lost more than 100 years ago

NETT LAKE, Minn. (June 7, 2022) — The Bois Forte Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, in partnership with The Conservation Fund and the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, along with its subsidiary Indian Land Capital Company (ILCC) announced today the completed purchase of land that restores to the Band more than 28,000 acres of land within the Nett Lake and Deer Creek sectors of the Bois Forte Reservation.

The Band’s acquisition of 28,089 acres previously held by timberland owner and lumber manufacturer PotlatchDeltic Corporation constitutes the largest restoration of land since the Nett Lake and Deer Creek sectors of the Bois Forte Reservation were established in Minnesota under the Treaty of 1866. Plans are underway for the Band to directly manage the restored lands under a forest management plan that emphasizes conservation and environmental protection balanced with economic and cultural benefits to the Band and its members.

“This is a historic day for the Bois Forte Band,” said Cathy Chavers, Chairwoman of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa. “This acquisition represents the largest restoration of land to our Reservation since our ancestors secured what was to be our permanent and undisturbed homeland. This acquisition rights a historic wrong and returns lush forests to the Band to foster and protect in homage to our ancestors and as an inheritance to our future generations. On behalf of the Band, I offer the deepest thanks to all those who made this day possible, especially those at The Conservation Fund and the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, whose efforts have been instrumental in making this historic restoration happen.”

The Band entered into a treaty with the United States in 1854 that set aside a region around Lake Vermilion as a reservation, which was later defined through an 1881 Executive Order. In its 1866 Treaty with the United States, the Band reserved two additional sectors at Nett Lake and Deer Creek to serve as its permanent homeland. However, just 20 years later, the federal government changed course, dividing the Reservation land and selling it to timber companies and homesteaders under the General Allotment and Nelson Acts. PotlatchDeltic eventually came to own significant acreages on the Nett Lake and Deer Creek sectors of the Reservation.

While some land was restored to the Band in 1938 under the Indian Reorganization Act, control of significant swaths of land within the 111,787-acre Nett Lake and 22,927-acre Deer Creek sectors remained out of Band ownership. But an opportunity for the Band to regain 28,089 acres – 21% of the total land base within the Nett Lake and Deer Creek sectors – emerged after PotlatchDeltic sold most of its land in Minnesota to The Conservation Fund in 2020. The national environmental nonprofit acquired over 72,000 acres of forestland, including 28,089 acres within the Bois Forte Reservation (27,565 acres in Nett Lake and 524 acres in Deer Creek). Conversations between the Band and the Fund about the lands within the Reservation began shortly thereafter.

“This outcome honors the heritage of this land by reuniting it with the Bois Forte Band and ensuring its long-term stewardship,” said Larry Selzer, The Conservation Fund’s president and CEO. “As a mission-driven organization, we are focused on creating solutions for naturally and culturally important lands that make sense for the environment and communities. We respect the Band as the best possible caretakers for this forestland and celebrate together this historic milestone.”

The Band’s purchase was financed by the Indian Land Capital Company, a Certified Native Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) providing alternative loan options to Native Nations for tribal land acquisition projects. ILCC is owned by the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, a national, community-based organization serving tribal nations and people in the recovery and control of their rightful homelands.

“As we work to ensure more Indian lands return to Indian hands, today’s announcement demonstrates a meaningful step on the long journey ahead,” said Cris Stainbrook, President of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. “We are proud to have helped the Bois Forte Band reach this milestone moment and hope that it inspires many more like it throughout Indian Country. And, it reminds all of us that restoring land to Indian ownership, management and control is more than a hashtag, it is a reality.”

A combination of conservation incentive payments under the Minnesota Sustainable Forest Initiative Act, coupled with other sustainable revenue streams that can be derived from the forest, will allow the Band to fully fund this acquisition and promptly pay off the purchase price. Later, the revenue generated from the land will support the Band’s land acquisition and conservation efforts.

The Bois Forte Band, a federally recognized Indian tribe organized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, has over 3,600 enrolled members. The Band’s governing body is the Bois Forte Reservation Tribal Council. Among its other duties, the Council works to identify opportunities to restore the Band’s historic land base lost to federal allotment policies in order to ensure proper stewardship of those lands, expand economic opportunities. and exercise greater control over the Band’s territory.

The Bois Forte Reservation includes three sectors: Nett Lake, Deer Creek, and Vermilion, which are located in parts of Minnesota’s Koochiching, Saint Louis and Itasca counties. The Nett Lake sector is known for its prolific production of high-quality and hand-harvested wild rice, which is of vital traditional, cultural, and economic importance to the Band and its members.

About the Bois Forte Band

The Bois Forte Band of Chippewa is a federally recognized tribe situated in northern Minnesota. The Band’s governing body is comprised of a five-member Council. The Band delivers government services to over 3,600 enrolled members who are located on-reservation, across the United States, and abroad. The Band provides government services through a variety of departments, including Bois Forte Health Clinic, Human Services, Police Department, DNR, Tribal Court System, Realty, Housing, Enrollment, Public Works, IT services, Accounting, Education and Human Resources. As the owner and operator of the Boys and Girls Club, Fortune Bay Resort Casino, the Y-Store, and the Nett Lake C-Store, the Band is one of the largest employers within its region. You can learn more about the Band by visiting its website at: http://www.boisforte.com/.

About The Conservation Fund

At The Conservation Fund, we make conservation work for America. By creating solutions that make environmental and economic sense, we are redefining conservation to demonstrate its essential role in our future prosperity. Top-ranked for efficiency and effectiveness, we have worked in all 50 states since 1985 to protect more than 8.5 million acres of land across the U.S., including nearly 392,968 acres in Minnesota. www.conservationfund.org

About the Indian Land Tenure Foundation

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is a national, community-based organization serving American Indian nations and people in the recovery and control of their rightful homelands. ILTF works to promote education, increase cultural awareness, create economic opportunity, and reform the legal and administrative systems that prevent Indian people from owning and controlling reservation lands.

Media Contacts:

- Brian K. Anderson, Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, 218-753-7882, bkanderson@fortunebay.com

- Joshua Lynsen, The Conservation Fund, 301-675-7764, jlynsen@conservationfund.org

- Grant McGinnis, Indian Land Tenure Foundation, 320-808-7825, gmcginnis@iltf.org

Map & Images: https://bit.ly/3GBTERz

Watch a video of the historic ceremony.

This news release was originally published by the Bois Forte Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe and is reshared here with permission.

———————————————-

TRIBAL AG EXTENSION PROGRAMS NEED FEDERAL FUNDING BOOST, EXPERTS SAY

Tribal Business News

Jan. 31, 2022

By Chez Oxendine

Little Canada, Minn.-based Indian Land Tenure Foundation has two contracts going with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The first is to provide legal services, such as will-writing and gift deeds for Native farmers and ranchers. The second is to support the USDA’s Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Programs (FRTEP) and their agents.

FRTEPs serve as tribal parallels to the National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s county extension program, which is administered by land-grant universities and colleges. These programs provide localized agricultural services and research, such as planting information and weather data, to producers in a given area.

While the USDA currently lists nearly 3,000 county extension programs across the United States, only about 30 such FRTEPs exist in territories controlled by the country’s 574 federally recognized tribes.

“We just don’t have the coverage that the rest of the country does,” said Cris Stainbrook, president of Indian Land Tenure Foundation. “FRTEP is so poorly funded compared to the rest of the extension program that when they start talking about tribes participating and working in getting that information out to folks, it’s truly lopsided.”

The inequity presents a problem because tribal extension programs can serve as “lifelines” into communities, said Maureen McCarthy, director of the Reno, Nev.-based Desert Research Institute Native Climate program, a nonprofit climate and environmental research organization.

FRTEP agents often live on the reservations where they work and administer the extension programs, and serve as liaisons to the educational institutions, some of which are tribal colleges and universities. The agents frequently prove themselves to be the best advocates for a community’s needs and issues, according to McCarthy.

“It’s a program that is underappreciated. This is the lifeblood, this is how you hear what the community needs,” McCarthy said. “(The Desert Research Institute) works with FRTEP agents extensively in determining how best to help these communities.”

Having direct insight into a community’s most pressing needs serves as a shortcut through “red tape” that may otherwise delay badly needed aid, McCarthy said. She cited programs prompted by COVID that might have stalled in the bureaucratic process before reaching people in need if not for the local knowledge and community presence of FRTEP agents.

“We started a working group in March 2020, weekly Zoom calls with FRTEP agents from the land-grant universities and tribal colleges we work with. We took those urgent needs straight into USDA and other agencies,” McCarthy said. “We started programs where we just cut through a lot of red tape. We got resources onto the Hopi Reservation when their roads were closed — we got relief packages all the way up to Alaska.”

FRTEP agents positioned in those communities provided localized guidance, McCarthy said, noting each agent serves as a link between the range of agencies and institutions providing assistance and tribal members.

“We couldn’t have done it without these agents,” McCarthy said.

‘Underappreciated and under-resourced’

FRTEPs are funded through four-year competitive grants administered by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture within the USDA. As of this writing, NIFA funds 36 FRTEPs across the country, 33 of which are located on tribal reservations.

Funding for the grants is comparatively tight, especially given the areas in need of coverage. The most recent Congressional appropriations bill allocated $3.2 million in total funding for the FRTEPs. By comparison, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack’s most recent request for county extensions stands at $315 million. While the Cooperative Extension program pays more than 15,000 full-time employees, only 30 or 40 people are employed by FRTEP nationwide. (The USDA did not respond to requests for comment by press time.)

FRTEP was established as part of the 1990 Farm Bill, which outlined a program supported by a $10 million appropriation and a network of 90 agents across the country. However, FRTEPs have never received the initially promised $10 million annual budget, according to a 2016 Indian Land Tenure Foundation report.

Funding for FRTEPs peaked at around $3 million annually in 2005.

As a result of this meager funding, adding an office on a new reservation or territory often forces one to close somewhere else in Indian Country, according to Stainbrook.

Moreover, each agency typically employs one agent, and the funding awarded by each grant serves primarily to cover that agent’s salary and not much else.

“They have to find creative ways to develop their programs,” McCarthy said. “There’s like one agent per reservation, and there’s not 100 percent coverage to all of our communities. Tribal extension, as a whole, has been underappreciated and under-resourced in comparison to the major investments in cooperative extension that’s been made for decades by USDA.”

The lack of coverage delays or even halts the flow of information to participating communities. Farmers use that information for developing everything from planting to grazing strategies, Stainbrook said.

“The USDA talks about county extension programs being ‘key’ to getting information out,” Stainbrook said. “If we don’t have a comparable track in Indian Country, we’ll get that information late or it may never get to the reservation. If they’re key to the other producers, shouldn’t they be key to Indian Country as well?”

Organizations like the Indian Land Tenure Foundation are stepping up to help provide direct funding for agents. For example, Stainbrook said the organization recently purchased a rototiller for one agent. Even so, he acknowledges that private funding won’t be enough to close the gap.

In response, Stainbrook and others are advocating to change the structure of the FRTEP grants to allow for more projects in more territories through a multi-agency commission sponsored by the Native American Agriculture Fund.

“The commission is really to look at the FRTEP program itself going forward and expanding,” Stainbrook said. “It’s really to come up with what we want to see over the next ten, twenty, fifty years, and then begin getting that put into the next Farm Bill.”

The commission’s primary goal is determining how to expand and “uncap” FRTEPs, allowing for an increased budget and expanded employment.

“We want to solidify these existing programs so they don’t go away when someone new applies for funding,” Stainbrook said. “We want these FRTEP agents to have tenure and support the same way cooperative extension agents do.”

The commission, which draws its membership from Native agricultural agencies, FRTEP agents, and a NIFA adviser, wants to see greater equity between FRTEPs and the cooperative extension, which starts with expanding the grants and securing more funding, Stainbrook said.

Although Stainbrook estimates that tribes could use “75-100” FRTEPs to approach parity with county extensions, McCarthy aimed even higher.

“Every tribe in the nation should have a minimum of one extension agent, a FRTEP extension agent or access to an agent” through tribal land-grant colleges, McCarthy said. “This should not be negotiable.”

Each of those potential agents represents a valuable asset for the tribe they’re attached to, which makes expanding the program “critical,” Stainbrook said.

“They’re a committed group of people, more than I’ve ever seen in a lot of places, and that’s what keeps us involved,” he said.

———————————————-

ILTF SELECTED BY USDA TO PROVIDE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FOR NATIVE FARMERS AND RANCHERS

Jan. 5, 2022

LITTLE CANADA, MN – The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is one of 20 organizations selected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide underserved farmers, ranchers, and foresters with the tools, programs and support they need to succeed in agriculture. The USDA has allocated approximately $75 million in American Rescue Plan funding for this initiative. Organizations, including ILTF, were selected for their proven track records working with underserved producer communities.

Massive amounts of reservation lands that were guaranteed by treaty and executive orders for “the exclusive use and occupation by Indian people” are now owned or leased by non-Indians for agricultural production. The resulting loss to the Indian agricultural economy was estimated at $8.5 billion in 2017 (last year of data availability). This compares to the approximately $1.3 billion generated by Indian farmers, ranchers and tribal operations. Native farmers and ranchers are not just socially disadvantaged but often actively discriminated against in both policy and practice. Even federal policies enacted with good intentions have often resulted in further disadvantaging Indian farmers and ranchers and impeding economic growth.

For nearly 20 years, ILTF has been providing information and technical assistance to Native Nations and individual Indian landowners focused on management and control of their land assets, much of which is agricultural land. ILTF has provided numerous publications, website content, landowner workshops (both on-reservation and online), assistance with Agricultural Resource Management Plans, as well as estate planning services to prevent further fractionation of Indian land. This USDA funding will enable ILTF to do even more.

———————————————-

ILTF RAISING FUNDS TO SUPPORT RETURN OF ‘PICTURE CAVE’ CULTURAL SITE TO THE OSAGE NATION

Sept. 13, 2021

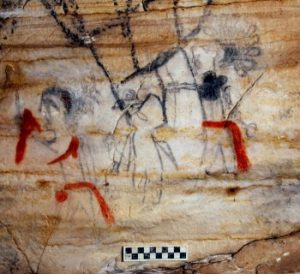

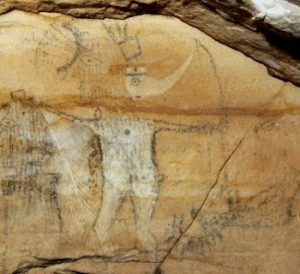

Tucked away within a 43-acre tract of woodlands in rural Warren County, Missouri is Picture Cave, one of the most significant cultural and archeological sites in the eastern United States. Today Picture Cave is in danger. The family that owns the property is determined to sell it on the open market and is putting it up for auction to the highest bidder without regard to the history and importance of the site. The cave art is believed to be the work of ancestral Osage peoples who traveled to Picture Cave to carry out sacred rituals, rites of passage and vision quests, to commune with spirits in the “other world” and to bury the dead. Indian Land Tenure Foundation is supporting the Osage Nation’s efforts to reacquire this important cultural site.

Located just west of St. Louis, this “dark zone cave” (a cave that has no natural light) contains 299 individual pictographs (paintings) grouped into 12 panels on several walls of the cave. Using accelerator mass spectrometric radiocarbon analysis, archeologists have determined that the paintings date back at least 1,000 years.

Located just west of St. Louis, this “dark zone cave” (a cave that has no natural light) contains 299 individual pictographs (paintings) grouped into 12 panels on several walls of the cave. Using accelerator mass spectrometric radiocarbon analysis, archeologists have determined that the paintings date back at least 1,000 years.

Picture Cave is also home to a significant population of endangered Indiana and gray bats that reside in the cave during the winter months. Although the cave entrances have been gated to deter humans from entering, the gates are not designed with access and airflow requirements the bats need to survive. Once the site is back in the hands of the Osage, the Nation will install appropriate bat gates to restrict human access and save the bats.

Working together with The Conservation Fund (www.conservationfund.org), ILTF is helping to raise sufficient funding so that Picture Cave can be returned to the Osage Nation to be protected and preserved forever.

To support these efforts, donors can click here to contribute to ILTF’s Land Recovery Fund. 100 percent of contributions will support the Osage Nation’s reacquisition of Picture Cave.

———————————————-

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL: AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

July 16, 2021

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is requesting proposals for preparation of its yearly audited financial statements and related information for the 2021 fiscal year ending December 31, 2021. The audited financial statements must be prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. The audit must also include an expression of an opinion by the auditor on the fairness of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles.

ILTF is a 501(c)(3) Minnesota community foundation providing grants and services to federally-recognized Native American Tribes and other organizations working with Native American land issues throughout the United States. We receive funding from individuals, foundations, Native American Tribes and other organizations interested in helping us fulfill our mission. We also pursue funding from the federal government when the opportunity arises. ILTF is also a partner in the Indian Land Capital Company, a for-profit organization which it organized as a subsidiary to provide financial lending services in Indian Country.

ILTF requires the following services:

- Yearly financial audit, including

- Consolidated statement of financial position

- Consolidated statement of activities

- Consolidated statement of functional expenses

- Consolidated statement of cash flows

- Supplemental statements separating parent and subsidiary

- Single audit (if applicable)

- Preparation of IRS form 990

- Preparation of Charitable Organization Annual Report for the Minnesota Attorney General

- Preparation of IRS form 1065 for subsidiary organization

- Preparation of subsidiary organization’s partnership tax return for applicable states

- Management letter

The final audit report(s) and management letter must be completed within four months of the end of each fiscal year. The tax returns must be completed and filed by August 15. ILTF requires that a meeting of the auditors and selected ILTF staff be held to discuss a draft version of the audit. ILTF also requires that the auditors meet with ILTF’s Audit Committee each May in conjunction with our board of directors’ meeting.

All audit proposals must include:

- Firm’s qualifications to provide the above services

- Background and experience in auditing, particularly of nonprofits

- Size and organizational structure of auditor’s firm

- Statement of firm’s understanding of work to be performed, including tax and non-audit services

- A proposed timeline for fieldwork and final reporting

- Proposed fee structure for these services, with projected costs for future audits covering at least two years, with a maximum fee to be charged

- References from at least three comparable audit clients

Please mail your proposal to: Indian Land Tenure Foundation, 151 East County Road B2, Little Canada, MN 55117

Proposals must be received by August 15, 2021. Our Audit Committee will review all proposals and make a recommendation regarding the choice of auditors to our full board of directors in September.

If you have any questions or would like further clarification of this request for proposals, please contact D’Arcy Bordeaux at 651-789-1742.

———————————————-

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION TO HOST TRIBAL LISTENING SESSION MARCH 24

March 9, 2021

The U.S. Department of Transportation will hold a virtual listening session on March 24, 2021 as part of the DOT’s efforts to develop a detailed plan of actions to strengthen the nation-to-nation relationship between the Department and Tribal nations. This effort stems from the Jan. 26, 2021 Presidential Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening of Nation-to-Nation Relationships (Executive Order 13175). The Tribal consultation session will be held from 2 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time. Participants can access the online presentation at www.transportation.gov/self-governance.

Click here to read the Feb. 28, 2021 letter on the subject sent to tribal leaders by Arlando Teller, Deputy Associate Secretary, Tribal Affairs.

———————————————-

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PROPOSES CHANGES TO PROBATE REGULATIONS

Jan. 28, 2021

The Department of the Interior (DOI) is updating regulations governing probate of property that the United States holds in trust or restricted status for American Indians. Since the regulations were last revised in 2008, the DOI identified opportunities for improving the probate process.

These proposed revisions would allow the Office of Hearings and Appeals (OHA) to adjudicate probate cases more efficiently. The proposed revisions would also enhance OHA’s processing by adding certainty as to how estates should be distributed when certain circumstances arise that are not addressed in the statute.

The Department will hold a tribal consultation session, a public hearing and provide the opportunity to submit comments. The Indian Land Tenure Foundation encourages Indian landowners to participate in this process.

Important Dates

- Feb. 9, 2021 – A tribal consultation session will be held at 1 p.m. (Central time)

- Feb. 11, 2021 – A public hearing will be held at 1 p.m. (Central time)

- March 8, 2021 – Deadline to submit written comments

Submit comments

You can submit comments in the following ways:

- Via the Federal Rulemaking Portal: www.regulations.gov (The rule is listed under Agency Docket Number DOI– 2019–0001)

- By email: Tribes may email comments to: consultation@bia.gov. All others should email their comments to comments@bia.gov

- By mail or courier: Ms. Elizabeth Appel, Office of Regulatory Affairs & Collaborative Action, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street NW, Mail Stop 4660 MIB, Washington, DC 20240

Please note: ILTF is not accepting comments on this proposal. Please use one of the above methods to make a submission.

Click the link below to download a pdf of the Draft Probate Regulations.

Draft Probate Regulations 1.7.21

———————————————-

INDIAN PROBATE WEBINAR: PRESENTER REPONSES TO VIEWER QUESTIONS

On Jan. 14, 2021 the Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) and the National Tribal Land Association (NTLA) co-hosted the webinar, “Navigating the Probate Process.” The webinar elaborated on the Indian probate process and some of its institutional challenges, along with current and long-term challenges to the probate process overall. The panelists discussed the importance of properly executed wills and their storage, and provided an idea of what happens during a hearing and decisions stemming from it.

The panel included three representatives of the Probates and Hearing Division of the Office of Hearings and Appeals: John R. Payne, Chief Administrative Law Judge (Sacramento, CA); Mary Thorstenson, Acting Supervisory Indian Probate Judge (Rapid City, SD); and Christine Kelly, Supervisory Paralegal Specialist (Albuquerque, NM). The panel was moderated by Nichlas Emmons, Program/Development Officer with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation.

As part of the webinar, viewers were able to submit questions to the panelists who have since provided detailed answers. Click the link below to access a pdf of the Q&A.

Navigating the Probate Process Webinar_Q&A

Click here to watch a video of the entire webinar

Click here to access the presentation slides

Additional questions about the webinar can be directed to Nichlas Emmons of ILTF via email to nemmons@iltf.org.

———————————————-

HAVING A WILL HAS NEVER BEEN MORE IMPORTANT FOR INDIAN LANDOWNERS

Dec. 15, 2020

With the COVID-19 pandemic taking a drastic toll across Indian Country, it has never been more important for Indian landowners to have a will. That fact has been driven home by the premature death of so many people in tribal communities, including several who were in the process of writing their wills with assistance from the American Indian Wills Clinic at Oklahoma City University School of Law.

Casey Ross (Cherokee) is Director of the American Indian Law and Sovereignty Center at the University. The clinic provides estate planning services to American Indians in Oklahoma who own an interest in trust or restricted allotment lands. “Our clinic slated several clients for services in the Spring 2020 semester, but due to the pandemic, services were interrupted by closures and restrictions on travel,” Ross explained. “During our hiatus, four of our clients passed away prior to completing their wills, some passing from complications of COVID-19.”

The clinic, which is supported in part by the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and the Oklahoma Bar Foundation, recognized the difficulties that the coronavirus pandemic has presented for clients and took action to resume providing services in a new way. As soon as it was safe, the clinic instituted drive-through services for the execution of wills by Indian landowners.

Adhering to a strict regimen of safety protocols, clinic workers were able to provide services at three different locations in Oklahoma where clients could sign and submit the necessary legal papers to execute wills without having to leave their vehicles. “We resumed services as soon as restrictions were lifted, and put into place protocols designed to keep clients, students, and staff safe,” Ross said. “Our ‘drive-through’ services have been appreciated and embraced. Since resuming services, we have experienced higher demand, and 100 percent of our scheduled clients have shown up for a service date in rural tribal communities. Folks are focused on taking care of this important task during this uncertain time.”

Writing a will enables landowners to determine who inherits their land

For many tribal citizens, their land is the most important thing they own. If Indian landowners pass without a will, however, it is up to a federal probate judge – not the landowner or their potential heirs – to determine who will inherit the land. It often takes years to reach a decision.

This year Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) introduced a new tool that can make it easier for Indian landowners to have a will. Developed in conjunction with legal services organizations across Indian Country, Will in a Box is now available for American Indians who own trust land in Montana, Minnesota and Oklahoma. Individuals who own trust lands in other states can also use the tool to organize and plan their will prior to consulting with a legal provider in their area. Hosted on the Law Help Interactive web platform, Will in a Box is available free of charge to tribal members.

Click here to learn more about Will in a Box and how it can help tribal members write their will.

———————————————-

ILTF INDIAN LAND APPRAISAL WEBINAR

Nearly every land transaction in Indian Country requires an appraisal but the process can take the Department of the Interior (DOI) many months to complete. The question is why, and what can be done about it?

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation hosted a live webinar on the subject of Indian land appraisals on Oct. 21 which can now be viewed here. The purpose of the webinar is to inform participants about why it is taking so long to get an appraisal completed and to explore recent changes within the DOI’s Office of Appraisal and Valuation Services as well as possible changes in the future. In addition, a portion of the webinar deals with the technical aspects of Indian land appraisal, including probate and valuation, structure and process, and the subject of mass appraisals.

The webinar presenters are Tim Hansen, Director of the Office of Appraisal and Valuation Services (OASV) which is part of the Department of the Interior, and Gregory Powell, who is the Regional Supervisory Appraiser of Navajo/Pacific/Southwest/Western Regions of OASV. The webinar was moderated by ILTF Program/Development Officer Nichlas Emmons.

Click here to view the webinar

Click here to view the presentation slides

————————————————–

ILTF RECEIVES $310,000 GRANT FROM THE BUSH FOUNDATION

Oct. 15, 2020

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) is one of 36 organizations selected by the Bush Foundation to receive an Ecosystem grant, which provide operating support to the programs and organizations that do the most to support the people of the Upper Midwest to creatively solve problems. ILTF has been awarded $310,000 over the next three years.

“The Bush Foundation has been a great supporter of Native organizations and Indian people in the region, and ILTF is grateful to have received a number of grants over the past 15 years,” said Cris Stainbrook, President of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. “We are pleased to partner with them to advance our mission of returning Indian lands to Indian hands.”

The Bush Foundation’s Ecosystem grants provide operating support for organizations that provide critical data and analysis, spread great ideas and build capacity, advance public awareness and policy, and build and support leadership networks. The grants are awarded through an open application process and grantees are selected based on how the organization operates, its impact on other organizations and leaders, how it fits with the Bush Foundation’s areas of focus, as well as the size of community and organization, demographics and location. ILTF has received four major grants from the Bush Foundation since 2006 totaling more than $1 million.

Based in St. Paul, Minn., the Bush Foundation invests in great ideas and the people who power them in Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and the 23 Native nations that share the same geography. Established in 1953 by 3M Executive Archibald Bush and his wife Edyth, the Foundation supports organizations and people who think bigger and think differently about what is possible in their communities. The Foundation works to inspire and support creative problem solving – within and across sectors – to make the region better for everyone.

————————————————–

PROVIDING PANDEMIC RELIEF: FRTEP AGENTS ARE PLAYING A VITAL ROLE DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS

August 24, 2020

Indian Country has been particularly hard hit by the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, but few people have been better positioned to provide assistance than Tribal Extension agents. As local leaders in the Federally Recognized Tribes Extension Program (FRTEP), these individuals have gone to great lengths to respond to the greatest needs on reservations across the country. From distribution of emergency food supplies and protective facemasks to helpful videos on how to make hand sanitizer and successfully grow your own food, extension agents have been a vital resource for Indian people, tribal leaders and government agencies.

Although the numbers are difficult to quantify, there is no doubt that much of Indian Country has been hit harder by the coronavirus than the majority of the nation. The combined impact of poverty, large numbers of individuals with pre-existing medical conditions, and inadequate medical facilities has been devastating.

“The medical systems are easily overloaded and there have been a lot of deaths,” said Trent Teegerstrom, Director of Tribal Extension at the University of Arizona, whose program serves seven different reservations. “For smaller tribes, the number of deaths has been more impactful as a whole because the population is small and everybody knows everybody. We lost one of our 4-H leaders and the tribes have lost cultural and language people. It has changed the way ceremonies and funerals are done and the people are trying to figure this all out. It’s just a complete paradigm shift.”

“The medical systems are easily overloaded and there have been a lot of deaths,” said Trent Teegerstrom, Director of Tribal Extension at the University of Arizona, whose program serves seven different reservations. “For smaller tribes, the number of deaths has been more impactful as a whole because the population is small and everybody knows everybody. We lost one of our 4-H leaders and the tribes have lost cultural and language people. It has changed the way ceremonies and funerals are done and the people are trying to figure this all out. It’s just a complete paradigm shift.”

Fortunately the FRTEP agents have been able to provide assistance. Some have distributed masks through food banks, soup kitchens and crisis shelters. Others have provided cloth and sewing materials so students in 4-H programs could make masks. At Hualapai there was no hand sanitizer available so FRTEP agents created a video to help community members make their own. Some agents distributed latex gloves and other Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to tribal communities while others organized the acquisition and distribution of emergency supplies of hay, firewood and food. In Alaska, the Bristol Bay tribal extension program has distributed more than 4,000 meals to youth and 3,000 pounds of produce to elders in remote communities.

“The networks we have with tribes and the USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) has been critical, and the relationships that have been built up over time have been integrated into a lot of the efforts taking place,” Teegerstrom explained.

Tribal extension agents have been working in conjunction with government agencies, non-profit organizations and corporations to coordinate logistics for emergency aid to tribal communities. “There has been a lot of collaboration,” Teegerstrom said. “One of the important aspects has been having that one person as a point of contact with the tribes. This situation really highlights the importance of maintaining that.”

Because of the way the FRTEP programs are funded on a two-year cycle of competitive grants, it can be difficult to ensure continuity of programming and personnel. That needs to change, not only to meet the short-term needs created by the COVID-19 crisis but the ongoing needs of the communities, as well. Even during the height of the pandemic response, agents are still serving farmers and ranchers, tribal youth and tribal communities with socially-distant services. Demand for information on how families can grow their own food has been greater than ever, programming for children and teens has been adapted for online delivery, and agents are finding new ways to communicate with stakeholders.

“This crisis has actually brought to life just how critical extension agents and programs are for the tribes,” Teegerstrom said. “We have known for a long time how important it is to have someone in there who has the education and access to the resources that tribes need. Now the USDA and others are finally realizing the importance of that, too.”

————————————————–

NATIONAL TRIBAL LAND ASSOCIATION, INDIAN LAND WORKING GROUP AND INDIAN LAND TENURE FOUNDATION CANCEL THE TRIBAL LAND STAFF ANNUAL CONFERENCE

March 12, 2020

Due to the rapidly increasing concerns related to the Coronavirus [COVID-19] outbreak, the increasing number of tribes with travel restrictions and the ever-increasing spread of the virus pandemic, the annual Tribal Land Staff Conference scheduled for March 24 through 26 at Mystic Lake has been cancelled. The National Tribal Land Association (NTLA), Indian Land Working Group (ILWG) and the Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) concluded that it would not be prudent to put attendees, speakers and staff at risk of contracting the virus either at the conference site or in travel to and from the conference.

NTLA, ILWG and ILTF will work together over the next several months to explore ways to share the information from the planned sessions with the conference registrants. ILTF will refund the conference registration fees in full in the very near future. The organizations will explore scheduling dates for the 2021 conference that will allow registrants with airline reservations to take advantage of the one-year grace period offered by some airlines for travel changes.

If you have any questions, concerns or other related issues, please contact Nichlas Emmons at 651-789-1754 or Cris Stainbrook at 651-766-8985.

————————————————–

ILTF ANNOUNCES LAUNCH OF THE TREATY SIGNERS PROJECT WEBSITE

Feb. 12, 2020

In 90 years, the U.S. property system spread across North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the U.S.-Indian treaties were essential events in this remarkable growth. What motivated such aggressive expansion, and who benefited from it the most? That is the question asked by the Treaty Signers Project.

Funded by the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, the Treaty Signers Project opens a surprising new window on the complicated history of US-Indian relations. The men who represented the federal government at treaties were not there by accident. They personified the powerful interests that directly drove the US acquisition of indigenous resources.

The treatysigners.org website presents information on hundreds of U.S. treating signers and on the business, family and social networks that connected them. It also provides basic information on each of nearly 400 treaties, plus stories that show why knowing who signed the treaties is important.

Beyond the American Myth: The real economic forces that drove U.S. expansion

The Treaty Signers Project examines how business interests in land speculation, railroads, the fur trade, mining, forestry and other pursuits heavily influenced the treaty making process and were largely responsible for the loss of so much Indian land. The “American Myth” presents “pioneers” as the driving force of America’s past. By contrast, the Treaty Signers Project presents the economic engines that actually drove U.S. expansion – interests that saw both Indian land and pioneers as sources of personal profit.

The 2,600 men who represented the U.S. in treaty negotiations secured hundreds of millions of acres of land for themselves, their families and their business partners – land that was sold to pioneers at a profit and includes the original sites for hundreds of cities and towns.

The Treaty Signers Project is helping researchers make sense of the vast amount of scattered information on these critical events. This innovative project will foster real discussion about our history as it actually was, not the idealized legends of westward expansion America celebrates today.

Click here to visit the Treaty Signers Project website.

————————————————–

Now hiring: Land Planning Program/Development Officer

Oct. 17, 2019

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation seeks to hire a highly motivated and skilled professional for the position of Land Planning Program/Development Officer.

Reporting to the President of the Foundation, the Land Planning Program/Development Officer will identify, cultivate, solicit and steward program initiatives for American Indian tribes throughout the United States being fully engaged in both programs and fundraising, including but not limited to: the creation and implementation of Foundation programs, grants management, provision of direct services to a variety of clients, development of communication and educational materials, leading the fundraising for each assigned program, reporting to funders of the programs, and measuring the effectiveness of the assigned programs.

Application deadline is Nov. 15, 2019.

Click here to read the complete position description and submit an application.

———————————————————————————

Standing Rock rancher started with nothing, now runs nation’s largest Native-owned buffalo herd

This article appeared in the Oct. 14 edition of the Fargo (ND) Forum

October 16, 2019

BULLHEAD, S.D. — A punishing winter piled up snow on Ron Brownotter’s pastures so high that half of his cattle starved because they couldn’t graze the frigid, windswept prairie surrounding the Grand River. A four-day blizzard stacked drifts as tall as a house, blocking roads to his pastures during the winter of 1996-97. “That changed everything for me,” he said. “I knew I had to diversify from beef cattle.”

The hard lessons from that disaster helped persuade Brownotter to switch to raising buffalo, the rugged “Monarch of the Plains” that adapted to thrive in the unforgiving environment of the Dakota prairies. “They take care of themselves,” he said. “They’re hardy; they’re strong.”

Today, the Brownotter Buffalo Ranch on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation sprawls over 20,000 acres, home to a herd of 600. His herd is part of a buffalo resurgence at Standing Rock that also includes native herds owned by the tribe and others.

For Brownotter, raising buffalo isn’t merely about practicalities. It’s about his ancestry and identity, an extension of the days when the Standing Rock Sioux were sustained by buffalo herds that once roamed the Northern Plains by the millions. “I’m raising buffalo because I’m a Lakota-Yanktonai person on Standing Rock,” he said. “We’re surviving here. It’s who we were and who we are.”

Thanks to years of hard work, Brownotter is doing much better than surviving. His operation is believed to be the largest buffalo ranch solely owned by an American Indian in the United States and Canada, according to the National Bison Association.

It took years of struggle and help from financial partners to survive a gauntlet of challenges. When he started ranching more than 20 years ago, he was commuting from California, where he was attending college, and had to scrounge for posts to build a fence to hold his herd. “I started with nothing,” he said.

***

The roots of the Brownotter Buffalo Ranch span three generations. When many families at Standing Rock were forced to sell their land allotments, his grandmother bought 320 acres in 1917.

“She never sold out,” he said, referring to his grandmother, Annie Leaf. His ranch southwest of Bullhead in Corson County occupies an area called Leaf Crossing.

The parcel his grandmother bought, later inherited by his father, became the basis for Brownotter’s ranch when he got his start in 1994. He eventually bought the land from his family and gradually added more rangeland through leases and purchases from neighbors.

Brownotter’s father raised a small number of cattle, planted a large garden and leased pastureland to neighbors. They also hunted to keep food on the table. “A lot of times we went hunting deer on horses,” he said.

Growing up around cattle — and living in the midst of a sea of grass — imbued Brownotter with a strong urge to raise livestock at an early age.

“I knew I was going to be a rancher since I was 12 years old,” he said. “As a young person I would come out here and fix fence, on my own, without being told.”

He spent money that fell into his hands on items including a shovel and ax, which he regarded as investments in his future. “I knew I needed tools to become a rancher,” he said.

In 1994, while studying agriculture at Cal Poly in Pomona, Calif., Brownotter plunged into the cattle business with the purchase of 100 beef cattle using a loan from a federal loan program.

Whenever he could break away, he made the 1,500-mile commute, one way, back home to Standing Rock to tend his cattle. Family and friends helped when he was away, but being so far from his livestock nagged at him. “It was a constant worry,” Brownotter said. Also, he added, “My equipment wasn’t up to par.”

While at Cal Poly, as a class assignment on agricultural entrepreneurism, Brownotter persuaded his study group to draft a business plan for a buffalo ranch on Standing Rock. The idea was viable, but it would be years before he would pursue it.

A setback in his early ranching days came when he was denied a loan to build pasture fencing. Years later, Brownotter would join a class action lawsuit by American Indian farmers and ranchers alleging loan bias by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

He had already started building the fence, but had to rip it out. Then came the killer winter.

The impetus to turn to buffalo ranching came in 2000 or 2001. Brownotter and his wife, Carol, were out for a quiet drive to Bullhead. Carol, who was taking classes at Sitting Bull College, knew that it would be a good time to switch to buffalo. “I noticed buffalo prices were at a slump,” she said. The cattle losses in 1997 remained a painful memory, and she knew Ron had yearned to raise buffalo for years.

“I just felt that this was the time to make the change,” she said. “I just said it — ‘We should go into buffalo.’ ” It didn’t take Ron long to answer. “OK,” he said. “I’ll do it.”

That November, the Brownotters went to Custer State Park in the Black Hills for the annual buffalo auction, where they bought six buffalo yearlings. Brownotter fenced off 10 acres near their home.

They were buffalo ranchers.

“That was an amazing feeling,” Carol said.

Click here to read the original online version of this article and view video of an interview with Ron Brownotter.

———————————————————————————

When Rivers Were Trails receives prestigious award at the International Festival of Independent Games

October 16, 2019

St. Paul, Minn. – The International Festival of Independent Games – or IndieCade as it is often called – has selected the When Rivers Were Trails video game as the winner of its Adaptation Award, which honors “works that reimagine how a well-known tale, genre or system can be explored within the context of play.” The honor was given during Indie Cade, which was held October 10-12 in Santa Monica, California.

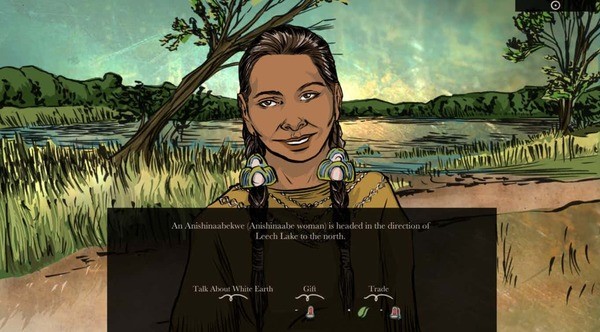

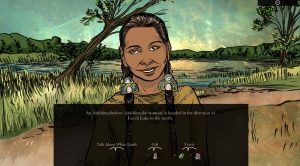

Developed by the Indian Land Tenure Foundation in collaboration with Michigan State University’s Games for Entertainment and Learning Lab, When Rivers Were Trails is an accessible, educational 2D adventure game that teaches young people about an important and often overlooked period of time in United States history.

Developed with support from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, the game follows an Anishinaabeg in the 1890’s who is displaced from Fond du Lac in Minnesota to California due to the impact of allotment acts on Indigenous communities. Players are challenged to balance their physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellbeing with foods and medicines while making choices about contributing to resistances, as well as trading with, fishing with, hunting with, gifting, and honoring the people they meet as they travel through Minnesota, the Dakotas, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and eventually must find a place to call home in California. The journey can change from game to game as players come across Indigenous people, animals, plants, and run-ins with Indian Agents. Gameplay speaks to sovereignty, nationhood, and being reciprocal with land.

Released in 2019, When Rivers Were Trails is available for PC/MAC, iPads, Android tablets and Chromebooks. More than 20 indigenous writers were tapped in the development of the game, bringing their valuable experience and perspectives to the project.

The game features creative directing by Nichlas Emmons, creative directing and design by Elizabeth LaPensée, art by Weshoyot Alvitre, and music by Supaman and Michael Charette. Indigenous writers include Weshoyot Alvitre, Li Boyd, Trevino Brings Plenty, Tyrone Cawston, Richard Crowsong, Eve Cuevas, Samuel Jaxin Enemy-Hunter, Lee Francis IV, Carl Gawboy, Elaine Gomez, Ronnie Dean Harris, Tashia Hart, Renee Holt, Sterling HolyWhiteMountain, Adrian Jawort, Kris Knigge, E. M. Knowles, Elizabeth LaPensée, Annette S. Lee, David Gene Lewis, Korii Northrup, Nokomis Paiz, Carl Petersen, Manny Redbear, Travis McKay Roberts, Sheena Louise Roetman, Sara Siestreem, Joel Southall, Jo Tallchief, Allen Turner, and William Wilson, alongside guest writers Toiya K. Finley and Cat Wendt who contribute African American and Chinese experiences.

———————————————————————————

Cow Creek Reservation (Photo courtesy of State of Oregon)

When public lands become tribal lands again

This article appeared in the August 16, 2019 edition of High Country News

By Anna V. Smith

The smell of scorched soil and burnt wood filled the air. Michael Rondeau, CEO of the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, looked over the damage, clad in forest-green pants and a lemon-yellow jacket with “Douglas Forest Patrol” on the back. The Milepost 97 Fire, which started just days earlier with an illegal campfire, had consumed almost 13,000 acres in southwest Oregon. Almost a quarter of that was on the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians Reservation — land so recently acquired by the tribe from the Bureau of Land Management that no conservation work or logging had yet occurred.

The tribe lost a good stand of timber, and officials estimate that replanting and recovery could take millions of dollars. Less than two months earlier, I had visited this tract of land, touring it with Rondeau and Tim Vredenburg, Cow Creek director of forest management. Then, it had been lush with evergreens and wildflowers — lupine, beargrass and paintbrush. Now, that was all gone.

“We’ve been so focused on managing to prevent fire,” Vredenburg told me over the phone, a few days after the fire. “That’s where all of our mental energy was being invested in: How do we manage this forest to prevent fire? And doggone it, now we’re looking at: How do we manage it after fire?”

The answer may lie in something Vredenburg and Rondeau said to me before the fire: that the Cow Creek lands would be managed differently now than they were by U.S. agencies prior to their return. Thinning and reintroducing fire through prescribed burns, they told me, would be a top priority for the more than 17,000 forested acres the tribe received through the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act in 2018. Rondeau explained that the management of Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians reservation lands would reflect Indigenous values: an example separate from either industry or conservation groups. “We don’t believe in locking up the forests and allowing them to ‘remain natural,’ because it never was,’” Rondeau said. “For thousands of years, our ancestors used fire as a tool of keeping underbrush down, so that the vegetation remains healthy and productive.”

Looking down from Canyon Mountain at a valley full of blackened madrones and pines, Rondeau and Vredenburg — along with some 1,800 Cow Creek tribal citizens — are thinking of the future, 165 years after their lands were taken and only one year after they were partially returned. The Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act’s passage illustrates just how long it can take — and the kind of political will it can require — to hold the United States and its citizens accountable for illegal treaty violations.

The journey to regain control of Cow Creek lands has been a long one. In 1853, six years before the state of Oregon existed, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians signed a treaty with the U.S. government. In exchange for a reservation, housing and health care, the Cow Creek ceded 800 square miles of land. But instead of complying with the terms of its treaty, the federal government sold Cow Creek lands to settlers through the Donation Lands Claim act, making the tribe landless. In 1932, Congress passed a bill to restore the tribe’s land base, only to see it vetoed by President Herbert Hoover. Litigation followed. “That really did set back our tribal members for quite a few decades,” Rondeau says. “There was a continuation of their lifeways, but the longer it went from the time of the treaty, they would lose more and more of their culture or just simply be blended in to the new life ways and assimilate.”

But last year, the Cow Creek made a breakthrough with the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act. The act — which passed the U.S. House seven times, only to die each time in the Senate — finally was signed into law by President Donald Trump. It restored more than 17,000 acres of public land to the Cow Creek Band, along with nearly 15,000 acres to the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians.

“This is pretty rare. It shouldn’t be, but it is,” says Cris Stainbrook, president of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, of the restoration act. “Those are the homelands of the tribe — these are lands that were reserved by the tribe in the treaty process.”

The Milepost 97 fire, then, was particularly devastating as a pointed reminder of the tribe’s long pursuit of land. During the Termination Era, which started in 1954 and affected tribal nations across the U.S., the federal government terminated 61 western Oregon tribes, abdicating its legal responsibility to Indigenous communities. (To date, five tribes in western Oregon have regained their federal status.) In the 1950s, former Oregon Gov. Douglas McKay, who headed the Interior Department, “enthusiastically” supported termination, after pushing state-level policies to “integrate the Indians into the rest of our population.”

Michael Rondeau represents one of the last generations of Cow Creek to remember what termination was like: no access to higher education or health care, and no land base — despite legal promises. His father, Tom Rondeau, the descendant of French traders and Umpqua people, grew up with a ramble of cousins on his grandparents’ Tiller, Oregon, homestead in the 1940s, hearing a mix of English, French and Chinuk Wawa, also known as Chinook Jargon. Tom, a big guy with a flattop, raised Michael and his brother in Glide, Oregon — 17 miles from where Michael now lives and works. The Rondeaus were a timber family, and Michael spent his childhood summers on the meandering North Umpqua River, a self-proclaimed river rat. By age 17, his dad had him setting chokers on Douglas fir trees to make sure he understood the hard labor he’d be doing if he chose to work in the timber industry.

Decades after termination, persistent efforts by tribal nations and advocates resulted in the federal government once again recognizing tribes and treaty obligations. In the 1970s and ‘80s, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde gained federal recognition again, along with some lands. The Coquille Indian Tribe, Cow Creek and Coos were re-recognized, too, but without lands. Efforts by tribes in what is currently western Oregon to reacquire their land came shortly after recognition.

In 1996, the Coquille Indian Tribe, based on Oregon’s southern coast, regained 5,400 acres of BLM land. But local voters opposed the transfer by nearly 5 to 1 in an advisory vote, and the final legislation required that the tribe allow public access for hunting, recreation and fishing.

An attempt by the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians to acquire federal lands the next year in 1997 hit a roadblock when voters and environmental groups vocally opposed the transfer, arguing that the land would no longer be subject to federal environmental law, despite promises from the tribal chairman that the tribe would adhere to federal standards. “Although the Coos tribe still hasn’t formulated details such as the amount of acreage or specific parcels of land,” a 1997 Associated Press article wrote, “environmentalists already say they would oppose any plan that would remove federal land from public control.” The Coos tribe would not receive their lands for another 21 years, until the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act.

In 2013, when the Cow Creek drew up plans for the BLM land transfer, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden’s office nixed the deal. The lands were ground zero for the timber wars of the 1990s, when the Endangered Species Act and industry clashed over the spotted owl, making their transfer almost 20 years later a non-starter for conservation groups. “It was such a touchy conversation with the environmental community — it would have been a complication that would have been hard to overcome,” Rondeau said. Instead, the tribe received BLM lands of relatively lower timber quality — checker-boarded lands, instead of the contiguous land base of many reservations.

The tribe also tried a less conventional approach. In 2017, the Cow Creek Tribe made a bid to buy Elliott State Forest, after the state of Oregon put it up for sale. The Elliott, which was legally required to make money for Oregon schools, hadn’t been producing enough. “Our tribal leadership was concerned that some out-of-state, out-of-the-area or foreign-owned company could come in and buy this forest,” Vredenburg said. With its $220 million price tag, the Elliott was out of reach, so the Cow Creek turned to Lone Rock Resources, a local Oregon-based timber company.

Conservation groups, critical of Lone Creek’s forestry practices, staunchly opposed its involvement and accused the partnership of wanting to privatize the forest. Conservationists in turn were called out for their failure to work with tribal nations: “Your organization has mobilized opposition to the sale, with little to no engagement with the Tribes who would have, once again, become the stewards of this land,” a consortium of racial justice groups, including NAACP Portland, wrote in an open letter to the Sierra Club, Cascadia Wildlands and four other conservation organizations. “We also note the many ways in which environmental groups in Oregon remain predominantly white, and work from a place of white privilege; this situation is a very clear example of the lack of racial justice analysis applied to what is a complicated situation.” Then-Sierra Club Oregon Chapter Director Erica Stock responded, “As an environmental conservation community, we must do more to proactively reach out to Tribal Nations and rebuild trust.”

Ultimately, the sale was dropped by the state after intense public outcry, but tensions between conservation groups and tribes remain.

“The conservation movement began as a way for settlers to justify the seizure of Indigenous lands under the pretext that Native peoples didn’t know how to manage them,” says Shawn Fleek, Northern Arapaho, who is director of narrative strategy for OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon. “If modern conservation groups don’t begin their analysis in this history and struggle to address these harms, it becomes more likely they will repeat them.”

Rhett Lawrence, conservation director for the Sierra Club’s Oregon chapter, says that his group opposed the timber company and privatization, not the concept of tribes regaining their lands. Still, Lawrence acknowledges, “We need to do better about having those conversations. We certainly have not resolved things from where they were two years ago.” Since then, two groups named in the open letter, Trout Unlimited and Wild Salmon Center, have now partnered with the Cow Creek Tribe on restoration projects.

Once a decade, a national study of tribal forests is conducted to monitor land health, production and management. The latest study, in 2013, found that the federal government was not fulfilling its trust responsibility to fund tribal forestry programs, yet noted that tribal stewardship could nonetheless serve as a model for resource management and practices on federal lands. “Those studies have shown that Indian forest management is superior than BLM and BIA because of the direct tie the Indian people have to the land,” says George Smith, chief forester for the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1978 to 1983 and the former executive director for the Coquille Tribe. “That’s their homeland, so they have a lot more vested interest in how those lands are managed.”

Tribes are often better at managing timberland holistically, says Smith, adding: “The tribal capacity with most of the tribes now, particularly the self-governance tribes, is at least equal to or better than the federal government.”